Authored by Jeff Brown CFA President & CEO, 18 Asset Management Inc.

David versus Goliath is a story of small being pitted against big and of small prevailing despite being up against seemingly impossible odds. Like the fictional David, real Davids prevail daily in business settings, a phenomenon easily illustrated by technology industry examples. Years ago, when then Davids, Apple and Microsoft took on industry Goliaths, IBM and Hewlett Packard, they prevailed, securing their spot in business success folklore.

In the 1990s, Facebook and Google were upstarts up against formidable foes. Now, they are multi-billion dollar organizations. Today, the cycle repeats with thousands of technology start-ups inspired by past David successes.

And this includes the investment management industry. However, while not every new manager will become a David, there are signals institutional clients can look for to find a winning David amongst all new managers.

Two Camps

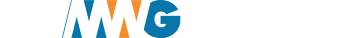

To begin, let’s examine why a client should even care about the Davids. What are the benefits? Using eVestment Alliance, we examined the returns of Canadian equity managers over the past 10 years, splitting managers into two camps. Goliaths were firms with total firm assets under management (AUM) exceeding $1.5 billion. AUM of under $1.5 billion defined a David.

The 10-year historical returns are shown in Chart 1. It shows Davids win. Small investment managers generated returns far surpassing their large counterparts. Our study is corroborated by a very large body of academic research conducted over the decades1 in various countries. In every asset class, these show

that small managers can produce superior returns without incurring additional investment risk. The research points to a number of contributing factors for this success. Small managers:

- Exhibit improved communications and quick decision-making enabling them to be nimble and rapidly implement new ideas, due to their team size

- Make smaller trades and incur lower transactions costs

- Are motivated to generate returns because they are invested alongside their clients and their reputations are at stake

- Possess skill and experience

- have a greater number of stocks to consider for portfolio inclusion

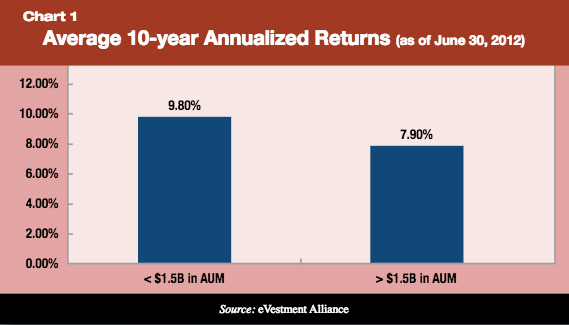

This last point merits further examination. Deciding to invest with a Goliath is partly a pursuit of prior investment successes and the perceived ‘safety in numbers’ bias conferred by their large AUM. However, the investment industry is “an anti-scale business – the bigger a manager gets, the more difficult it is to perform.”2 A Goliath’s large AUM indicates its asset gathering success, but potential for continued investment success drops as AUM rises due to the liquidity issues of managing an ever larger portfolio.

As AUM grows, an increasing number of stocks have to be eliminated from consideration because there isn’t sufficient trading volume to build a meaningful portfolio position. Chart 2 illustrates the liquidity situation in Canada. The vertical axis measures the number of stocks having sufficient trading volume to be included in a portfolio of a given size. The horizontal axis portrays growth in AUM. In a relatively illiquid market such as Canadian equities, AUM directly and negatively impacts choice. Manage $5 billion in AUM and choice drops precipitously, forcing large managers to congregate around the index’s largest stocks. Conversely, manage a small amount of Canadian equities and you have hundreds of stocks to choose from, a huge advantage in building a portfolio. This advantage cannot be replicated by large industry players because it comes solely from managing a small amount of money, an advantage the Goliaths lost years ago.

Despite the return premium, prospective clients may have perceptions that hold them back from hiring a new manager. These fears and perceptions are valid because not every small manager will thrive. Investors can address these perceptions using the Manager Search Checklist.

The Real Differentiator

Since 2005, we have been conducting research on investment process best practices. We draw the following conclusions from our efforts:

- A world class investment process is a pre-requisite for success in this industry.

- You have to continually invest in your process in order to keep up with world class standards.

- It is unlikely that its investment process will differentiate one firm from everyone else.

An auto industry example solidifies this last point. In 1900, auto manufacturing processes varied widely across manufacturers. Henry Ford then invented the assembly line, a process differentiation providing a competitive advantage of reduced costs. Process differentiation was possible in 1900. Advance the clock to today. Billions were invested in the auto manufacturing process over the last 100 years. Can one manufacturer’s process truly stand above the rest? No, the manufacturing process is near its maturity. The process differentiation opportunity is minimal, if not non-existent.

The investment process is comparable. We’ve been managing money for clients for longer than Ford has been making cars. Considerable research has been conducted aimed at advancing the investment process. Countless dollars and person years have been invested in improving investment processes in recent decades. The investment process is also near its maturity which means that there is little chance for process differentiation.

Ultimately, we conclude that culture is a firm’s greatest means of differentiating itself from its competition. Cultural necessities include:

- Having a clear and consistent vision guiding the business

- Aligning employees to the vision and guiding principles

How do you, as a prospective investor, ensure that a small manager is fostering a vibrant culture? Inquire about the following:

- Is the preferred culture defined in the business plan and are all employees aware of the preferred culture?

- Can examples be provided showing that senior management consistently ‘walks the talk?’

- Is there regular and frequent two-way communications about culture or is it just something discussed at the annual strategic planning session?

- If you believe that you should only expect that which you inspect, then ask if culture is part of the performance appraisal and compensation system.

The real benefits to hiring small managers is greater access to firm and portfolio decision-makers, enhanced transparency, and customized reporting.

Greatest Benefit

While the greatest benefit would be the opportunity to gain outperformance, to increase the odds of successfully investing with a new firm, the targeted small manager must recognize that having great returns and a world class investment process are not enough. They are merely entry stakes. Long-term business success requires making a significant upfront investment in a business plan that details remedies for common client perceptions about new, young, or small firms.

Ultimately, institutional investors have much (value added) to gain for the modest cost of getting to know some small, new managers well.

Manager Search Checklist

| New/Small Manager Perceptions | Remedies |

|---|---|

| They lack infrastructure to support portfolio management and administration. |

Look for managers that have:

|

| Employees have to wear multiple hats detracting from focus on client portfolio. | Can the small/new manager prove that their portfolio managers have support? Do they have an organizational chart with clearly defined roles? |

| Principals have experience managing money not managing a business. | Ask for the resumes of leaders. Do they have business management experience? Have they put in place business management infrastructure: audit, budget, annual financials, monthly MIS, Advisory Board and a strategic plan? |

| They lack a track record at current firm. | Prospective managers might not have a long track record at the new shop. Inquire about their history. Can they prove to you that they have capital resources to survive long enough to build a track record? |

| They lack resources (capital and people). | Will they share their business plan with you, one complete with how growth is going to be handled, new hires, capital structure, new products, etc.? |

| Due to low AUM the business might not be financially stable. Will they be in business in three years? | Entrepreneurs are keenly aware of this risk. As they have their own capital and reputation at risk, they may focus on this issue more than prospective clients do. This is good. Can the manager convey what they have done to mitigate this risk? Does their business plan contain a description of the systems, processes and capital that have been put in place to ensure their long-term viability? |

| Headline risk. Will the small manager one day go bankrupt, lose key personnel, or have a massive back office error? | Does the manager have a compliance culture, a rigorous compliance manual and procedures? Do they have a succession plan? Do they have key man insurance? |

1. Krum 2007, Aggarwal and Jorion 2008; Allen 2007; Newsome and Turner 2009; Beckers and Vaughan 2001; FIS Group Study on the performance drivers for small managers, 2007 to name but a few.

2. Tom Bradley, Globe and Mail, February 3, 2012, http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-investor/investment-ideas/for-money-managers-small-can-be-beautiful/article4202607/